Mythic Bastionland is the OSR Game I've Been Waiting For - Running the Game

Running Mythic Bastionland for the First Time Was a Triumph

Myths in Springtime

Shall I compare Mythic Bastionland to a summer day?

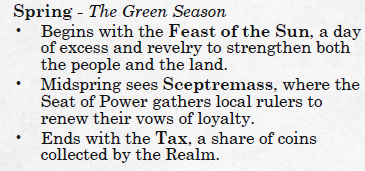

No, Spring is much better, I think. It is the first of three seasons, defined thus:

Study this and you'll learn everything you need to know about Chris McDowall's wonderful philosophy on game design. McDowall is sparing in his use of words; he won't ever use ten words when a single one will do. Not for him, verbosity.

It can be jarring. Especially if you've never played an OSR game, where sparsity is but one of the many rules of the game. I have, but not one of my two players for this. It's a leap to get used to the quirks of OSR as opposed to 5e design, where this player, A., comes from. OSR games seek to encourage emergent storytelling by unshackling the players from the limitations of an ability- and skill-based character sheet (as we have in 5e). On the other side of the screen, OSR games provide various tools to the game master (or Referee, as Mythic Bastionland prefers to call them) meant to facilitate story as it develops around the table as opposed to within the immaculate notes of a control freak GM.

Mythic Bastionland exceeds at providing both sides of the table with the necessary tools to this very end. McDowall's mechanics design is sparring but exact: there's no feeling of fatigue as you read through the twenty pages of rules that animate the game. His prose, meanwhile, is evocative, whether we look to his 72 knights, 72 myths, or the treasure trove of prompts you'll find waiting beneath those 144 entries. Never you mind the four Spark Tables that have 144 combinations each to inspire hexes and the landmarks within them.

I call McDowall's prose 'evocative', but it's more than that. Nor is it alone in being so: Alec Sorensen's art is the stuff of legends, or should be. Few rulebooks have such a uniform, unique identity as does Mythic Bastionland. I've spent hours scrolling across the rulebook and there's something hypnotic about each and every illustration. What's more, they light up the imagination like a lightning bolt, all of them. I often drew from Sorensen's pieces for my descriptions during the session, most memorably at what would turn out to be the climactic scene in my table's Dwarf*myth.

So much on my initial impressions. Onto discussing the prep and running of the game, I think.

A Smattering of Worldbuilding

(And a spoonful of character.)

One needs a hex map to play Mythic Bastionland. 12x12 is optimal, but if you're running the game for a smaller group or feel intimidated at the thought of populating a whopping 144 hexes, a smaller map is acceptable. No need to feel intimidated, however: McDowall doesn't expect you to create a hundred-page lore document, or a ten-page one, or even a five-page one. In truth, you need to roll a few dice, name a few geographic locales, and be prepared for a whole lot of improv on the table.

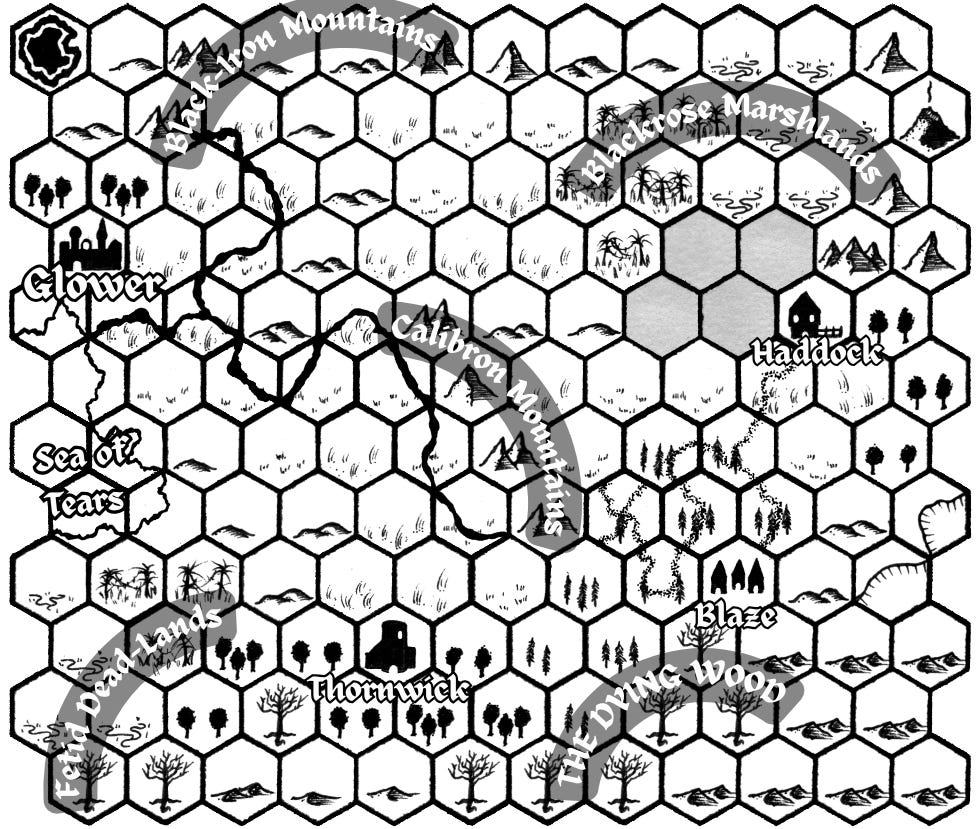

I prepared the following map:

This is the player-facing version of the map, note, as opposed to the one with all the goodies. I'll be keeping that one to myself for a little while longer yet, as my players and I are in the process of exploring it and I'd rather they didn't have the opportunity to peek beneath the curtain just yet. You'll notice I didn't do this by hand: instead, I used a nifty little piece of software I purchased on itch.io. It's called Hex Kit, by Cone of Negative Energy, and you can find it here. I discovered it whilst reading a Chris McDowall dev blog post about the beta of Mythic Bastionland from 2022, where he'd used this very piece of software to create a Realm for his players. You don't have to use this, however. If you're artistically inclined, you can just grab some hex paper and draw your own map by hand; or you could very easily use Mythic Bastionland's official Realm sheet (found here), which has a hex and all the icons you could ever need.

My hex-crawl map took me about an hour to prep, and even then I was a touch too slow. I could've been a lot quicker if I had used the rulebook's excellent Spark Tables rather than freezing several times mid-hex placement, trying to make conceptual sense of a world that doesn't have to make conceptual sense. I could've randomised the map entirely if I wanted to - Hex Kit has that option - but I like playing around with maps, so it was an hour well spent.

After it came the even more fun part: I rolled for six myths from page 27 of the rulebook, read through them, and placed them on the map. I also placed the Seat of Power and three other Holdings, named a bunch of geographic locales, and wrote a short introductory blurb to the Realm:

Sepulchria.

A Realm unkind.

Dangers await across its wilderness, manyfold and liable to steal the breath from a foolish Knight's breast.

You are Knights-Errant, armed with your blades and your wits and your Oaths.

They might not be enough.

And that was that, more or less. Landmarks, I decided to come up with during the session itself whenever they became relevant and necessary. This I did fairly well, as I will soon recount.

But first...

Meet the Knights-Errant

(Zero Kardashians were involved with this spin-off.)

Circumstances plotted against me in that five of my seven usual players couldn't make it. Three of them were known to be away for a long while, while the other two - yeah, those were planned, too, but in a shorter time-frame, and so this first session would prove to be among the most intimate I've run in recent memory.

Two players are pretty great when you have to learn the game. They give you and each other space and everyone listens: something that isn't always the case when you've got seven people surrounding you on all sides.

The back-end of Mythic Bastionland has the finest example of play section I've ever seen. I filched from it shamelessly in the initial minutes, stealing the explanation that the example referee gives their two players nearly word for word. It's a great introduction to how character creation works and I suggest you steal it too, if you're planning on running this game for the first time.

They rolled stats (S. rolled badly, A. rolled above the average for two of three stats). They then rolled to see which knights they would get: the War Knight and the Weaver Knight. Ironically, these fit their D&D characters (former in S.'s case, current in A's case) so well that we all had a chuckle. Their abilities had me salivating at the possibilities opening up before us. The Weaver Knight's ability, in particular, to exchange his weapon for another weapon that has a similar shape, might yet prove to be an absolute bastard of a skill as far as one of the Myths I rolled goes.

Evocative, those two Knights (like all others). Perhaps most evocative are the Seers, those wise and arcane folk who knighted the characters in the first place. The Armored Seer, found on the Weaver Knight's page, served to give them an initial boost: I rolled on a table, and narrated an omen as the Seer saw it with Sight that went beyond sight. (Plenty of this kind of fun poetic drivel spewing forth from mine mouth, note! What's the point of playing a Knight game if you're not going to ham it the fuck up??)

So off they were, my darling little knightlings, chasing after their first Myth: The Dwarf. How proud I was to give them a direction and see them go!

Knightly Deeds Done Dirt Cheap

(You don't have to pay knights for chasing myths around, promise!)

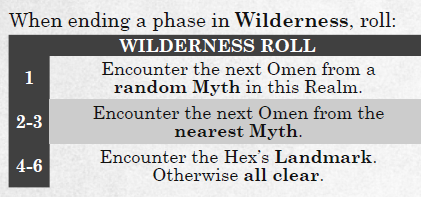

The Wilderness procedures the game has are incredibly simple to run, and so fantastically satisfying. They rely chiefly on the roll of the dice (d6) and on improvisation, itself made easy thanks to the dozens of prompts found at the bottom of each Knight and Myth page.

A. rolled a six, which meant I had to come up with . Let me tell you, the first time this happens across a new ruleset, my mind went blank for a good fifteen seconds. Even when it started working again, it wasn't clear sailing for a while. I kept losing words or mumbling them, suddenly self-conscious for no good reason. I rolled a d6 of my own, to decide between one of the six types of Landmarks they might've stumbled across:

The characters were in luck: I rolled a 1, so a Dwelling it was. Across the hillside they trekked, when suddenly a valley revealed itself to them, and in that valley, a secret vineyard attended by youths their own age. One of these, a girl by the name of Priscilla, hailed the Knights-Errant, and bid them join their mistress, the Knight who called the stone house next to the secret vineyard their home.

While the Knights waited for their host to join them, I figured this an excellent spot to give the players their first serious opportunity to find voices for these characters. This they did with aplomb--and when one player gave me an opening, I ably introduced their hostess, a fifty-year old knight with a good amount of scars across her body, three clay cups in one hand and a wineskin in the other.

Mildew, the Fanged Knight

(I kept wanting to call her Mildred, but what kind of knightly name is that? Thus, Mildew.)

Because Knights have knowledge of a random Myth across the Realm, I rolled to see which one Mildew would know about. This was one of the occasions upon which is founded my conviction that the dice wish to tell their own story, for it was the Dwarf that the Knight knew about. She spoke of him by name, and shared a certain fondness for the dwarf. She knew, too, of a landmark in the grasslands beyond this hinterland, the ruin of a tower once possessed by some primordial magic.

"Stand at the centre of this tower, and whisper thrice the name of the one you wish to find. An echo of music will sound in your mind, then; follow it and you will find the Dwarf." It was a fickle magic, she said, and to be used but once.

What a fun scene to play through, though: chivalrous and warm, it really captured the feeling of a mentor sitting down a pair of pupils and creating a bond with them that well might define how they view their (Knightly) roles. I had a fun time playing Mildew, and the players enjoyed interacting with a more experienced Knight who had a smattering of practical advice for them.

Trailing the Dwarf

With directions and welcome advice in tow, the Knights-Errant continued down the trail of the Dwarf. I won't recount all their travails, save to say that they butted heads with a group of mercenaries possessed of dwarf-forged arms; tensions ran high between the knights and the mercenaries, owing to rival ideologies about life, adventure, and everything in-between, with the mercenary leader, Endry, trying to worm his way into a favour from the Knights in return for information. Wisely, A.'s Weaver Knight, Trick, refused this (though he failed a Spirit save that might have gotten him one of the dwarf-forged spears that the mercenaries possessed).

The Knights continued their journey, and were awakened in the night by the third Omen of the Dwarf Myth - which was incredibly lucky in that it put them face to face with the object of their search. The Dwarf, having sniffed the smell of wine on their breath, rushed the Knights-Errant and demanded that they give him some wine. I figured, that relationship between the Dwarf and the Fanged Knight Mildew has already been defined, so why not play into it? Tense negotiations were thus lubricated by the judicious use of wine skins that Mildew had gifted our Knights (we rolled a Luck roll to retroactively see whether this had happened or not).

The negotiations were still somewhat rocky. I played the Dwarf as nervous, cantankerous, not entirely present. He is driven by obsession: the creative urge alone animates him. It became clear to the Knights that he wanted their aid, but the why was a little difficult to comprehend: only when they committed did the Dwarf fess up that he had felt tremors in the ground with his finely attuned senses, of danger nearing.

That danger came calling soon enough.

One Dwarf, Two Knights, Three Pissed-Off Giants

I was worried about this combat. Two Knights standing opposite three giants, all of the giants with a vigour of 17, a Guard of 7, and 3 Armor? Woof.

Turns out, I shouldn't have been. The combat system took us a pair of turns to figure out more clearly, but once we did, gods--what a revelation it is! First of all, it is simple: there's no "to hit" roll, you just roll your weapon and equipment's damage dice, and you look at the numbers. A few things matter here: first, to do damage, your die must be equal to or above the giant's Guard (in this case, 7). Second, any die over a 4 can be used to perform a gambit: one of several effects that have significant bearing for the opponent. There's Strong Gambits, too, and the War Knight can use those instead of normal Gambits, as long as there are at least three combatants on each side of the fight. This, S.'s Sir Tyron Mossberg grasped quickly and used to excellent effect to basically Impair the capacity of one giant to do him harm.

Once we figured out what we could all do, combat rounds flew by lightning fast. The Dwarf, who engaged with the giants, managed to deliver a few scars to his foes, breaking the spirit of one giantess who immediately turned and ran, afraid to be unmade. The Knights ably slaughtered first one giant, and then the other; and though the Dwarf lost more than half his health, they proved victorious in the end.

The Last Omen

What followed was an epilogue of sorts, with the fifth omen of the Dwarf's Myth seeing the players faced with the choice of how to best aid the refugees from a distant Realm. They were desperate folks, those, in need of warmth and hearth; yet Sir Trick managed to persuade them to wait a handful more days rather than to travel to the town of Thornwick by their lonesome.

This would prove a momentous decision, as the last omen saw the Holding closest to the Myth crumble into the ground, "swallowed into the distant Realm at the end of the tunnel". This the Knights and refugees saw from the utmost distance - but the shaking of the ground and the plume of smoke and dust in the distance was not lost on them. The horror of having aided the Dwarf, the realisation of having in effect saved the lives of the refugees: these created a powerful moment to close this first session on.

I wish now that I'd held off on the last omen. It was an effective way to close the session, certainly; but I can't help but wonder what it would've been like if the characters had seen the final omen arrive into their lives many years later, long after they had thought the Myth one and done. This is a question of immediate returns versus embracing a long play approach. Where this particular three-session campaign is concerned, the former worked out fine. If I was running a longer campaign, and this weren't my first time with the game, I would've banked on giving the Knights a triumphant victory against the giants, and a bitter realisation a long time after. Their glory and legend bloodied either way by association with the Dwarf.

If I have one regret, it's that I did a little bit too much of the talking during this first session. Not the latter half, perhaps, but I remember thinking at one point after the first half-hour, "Boy, if I'm tired of hearing the sound of my own voice, the guys must be about ready to strangle me". Maybe it's unavoidable - the players are uncertain and so are silent, and I'm uncertain, so I yap on and on. But they had fun and I had a fantastic time running this first session for them, and that's all that matters.

Very cool! You have definitely piqued my interest in MB. I love Chris’s work. Looking forward to more posts.